The discovery of debris in the western Indian Ocean that appears likely to be parts from MH370 has stimulated fresh interest in how such debris would drift, what these items might tell us about the demise of the aircraft, and what the possible implications are for the crash location.

Assuming that MH370 crashed into the ocean in an energetic impact creating a large amount of floating debris, I wanted to investigate where such debris would end up after two years.

The searchers for

AF447 recovered around a thousand pieces of floating debris following that crash into the Atlantic Ocean. There would have been more floating debris that they were not able to recover (for example, because it had already been dispersed from the crash location, or because it had subsequently sunk).

Method

I have used the drift model available from

www.adrift.org.au and in particular the dataset appropriate for a start in March from a position at latitude 37 degrees south near the 7th Arc (based on the outcomes of

my flight model). The ‘adrift’ model evaluates the probability of debris drifting across the ocean to specified end locations.

That dataset is available in two-month steps going forward from the start point and time. The drift outcome is defined in terms of a probability of reaching a certain location, defined as a cell 1° of latitude by 1° of longitude.

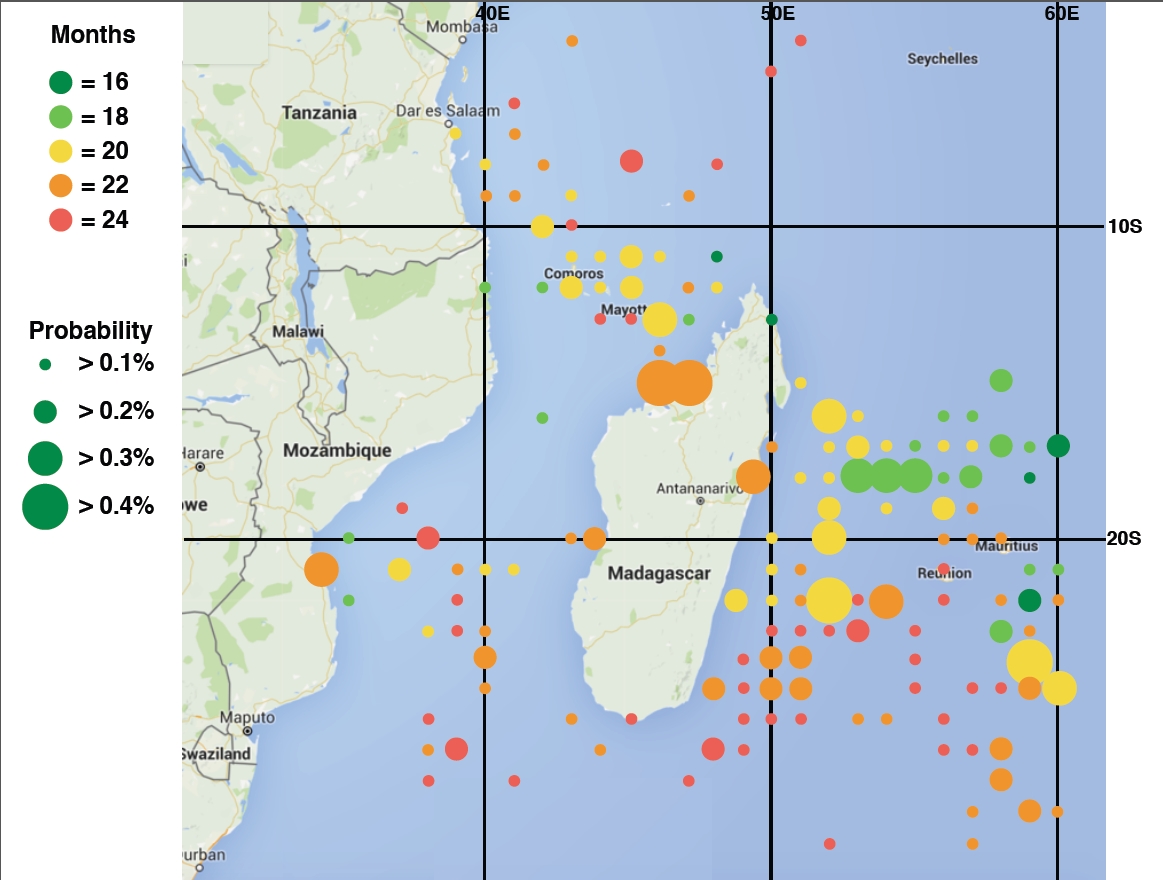

I have restricted my investigation to the timeframe from 16 months to 24 months after the MH370 crash (i.e. between last July, when the right flaperon was found in Réunion, and the present, with two additional candidate fragments having been identified in Mozambique and in Réunion).

The adrift model essentially ignores cells rendering very low probabilities, but for each two-month step the total probability summed over all cells at that time adds up to nearly 100%. I only used cells where the indicated probability was greater than 0.1% (i.e. 0.1% of the total number of objects in the overall area being investigated, as defined below; not 0.1% of all objects that started out drifting from the crash location).

Because of the general drift pattern and the find of the flaperon from MH370 in Réunion, I restricted my investigation to the western side of the southern Indian Ocean between latitudes of 04S and 34S, and longitudes between 33E and 60E. The total area included by those bounds is about nine million square kilometres; hereafter that region is termed ‘the area investigated’.

Results

The most likely location for debris to have washed ashore already (i.e. 24 months post-crash) is Madagascar, followed by the Comoros Islands and Mayotte, Mozambique, Réunion, and Tanzania.

The total probability that floating debris will be positioned in the area investigated is 5.8%; that is, out of one thousand floating debris items starting out at 37S near the 7th Arc, 58 may be anticipated to be within the area investigated (and 942 will be elsewhere).

Of the above 5.8% estimated to be in the area investigated, about 89% is expected, based on these calculations, to still be floating on the ocean, and only 11% already to have come ashore. That is, of the above putative 58 items there would be about six already come ashore, and 52 still on the ocean within that area investigated.

The map below shows the calculated spread of debris over the area investigated.

An Excel spreadsheet file is available

here, showing the various locations where one might expect debris to turn up on the shore.

Debris will still be arriving at the north-south line through Réunion or Mauritius (described in the Excel file as “Off Reunion” or “Off Mauritius”), but generally most floating items are now passing to the south and west; some will make first landfall in South Africa, while others may head out into the southern Atlantic Ocean.

Discussion

Assuming that MH370 resulted in 1,000 items of floating debris, then 58 items are likely to be in the area investigated.

However, only about six items would be expected have come ashore so far (Madagascar: 4, Comoros Islands: 1, Mozambique: 1, Réunion 0.5, and Tanzania 0.6). [DS: Before anyone starts shouting, these are expected figures based on an assumed one thousand items starting out. Obviously debris items are quantized in that one cannot have 0.5 or 0.6 of an item. On the other hand, it is also true that individual initial items might fragment upon reaching a shoreline. One might naïvely suggest that two items having been found in Réunion implies that at least 4,000 items of floating debris started out, but we are dealing with small number statistics here.]

The find of the flaperon in Réunion appears to have been extremely fortunate, and perhaps might imply there was a larger number of items of floating debris resulting from the MH370 crash; that is, many thousands of items.

The find in Mozambique (if it indeed turns out to be from MH370) is also against the odds, and Blaine Alan Gibson was certainly in the right place at the right time.

There are about four more items of debris perhaps waiting to be found on the north, east and west coasts of Madagascar; or, four multiplied by the number of thousands of initial floating items from the crash (assuming that none of the initially-floating items subsequently sunk).

Of the items of debris still out on the ocean — these comprising the majority — the ordering in terms of likelihood of landfall is as follows:

1. Madagascar

2. Mauritius

3. Réunion

4. Mozambique

5. Comoros Islands and Mayotte

6. Tanzania

7. South Africa

8. Aldabra

9. Seychelles

10. Kenya

That is, the locations at the top of that list are the most likely places to find more debris from MH370.

It is re-iterated that the above results were based on an assumed crash location as given in the title of this report. The results for crash locations within a degree or two of latitude of that assumed start point would be similar to those obtained here; but a start location far from that location (e.g. latitudes south of 40S or north of 25S) would lead to rather different results. That is, whilst the discovery of three items on coastlines in the western Indian Ocean (one confirmed piece from MH370 – the flaperon – and two items awaiting inspection and identification by the authorities) cannot be considered to demonstrate with certainty where MH370 crashed, the analysis presented here shows that their discovery, in terms of their locations and the elapsed time since the crash, appears to be consistent with the crash location having been around latitude 37S and close to the 7th Arc.